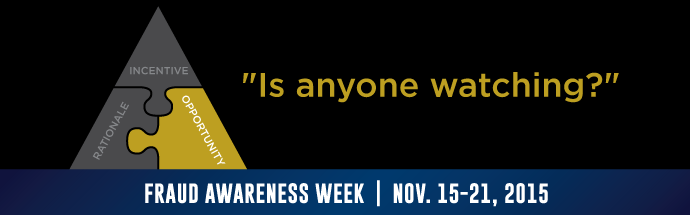

Opportunity for Fraud: Is Anyone Watching?

Donald Cressey’s Fraud Triangle historically has received a lot of attention during the ACFE’s Fraud Week and for good reason. It supplies a useful set of analytical distinctions in its three components—opportunity, rationalization, and pressure or motivation—that lead us to look at specific relevant factors that affect fraud in organizations. Understanding the causal forces at work helps us to take steps to address them.

The opportunity for fraud is the most straightforward causal factor for organizations to address because it is rooted in the organization itself. Unlike motivation or rationalization, opportunity does not depend on the potential fraudster’s personal circumstances or state of mind. Therefore, opportunity reduction works regardless of whether or not a potential fraudster exists in the workforce at any given time.

Opportunity has long played a part in the general policy of crime prevention. For example, in the 1980’s, a prominent theory was Crime Prevention through Environmental Design (CPTED). The aim was to create living and working spaces that removed opportunities for crime. In turn, CPTED was based on Jane Jacobs’ insight that safer cities were those that had vibrant, people-filled public spaces with lots of eyes on the scene. The idea that opportunity can be managed to reduce the incidence of crime, regardless of how potential criminals think or behave, has a solid pedigree.

It’s helpful to think about what defines an opportunity for organizational fraud:

- Something of value exists in the organization that can be removed and used by a fraudster. Usually money is the target, but intellectual property or physical items, among other things, might be taken.

- Employees (roles) have access to the things of value.

- Missing or inadequate controls make the target vulnerable. Metaphorically, there are not enough eyes on the street.

- Gaps in reporting, and responsibility to react to the reports, permit fraud to remain hidden. No one is watching the system’s performance closely enough to reveal the anomalies that indicate a fraud is occurring.

These dimensions or factors define the content of a fraud risk assessment that you will conduct in the first step toward implementing a prevention plan. Organizations have to take a clear, objective look at processes and the information they generate, as well as what roles have access and authority over those elements. The opportunities identified have to be addressed with specific procedural and/or physical measures that indicate when a potential fraud might be occurring.

Finally, no amount of planning or measuring can be effective without monitoring and reporting on indicators that may reveal that a fraud is occurring. Since fraud can happen at any time, these indicators have to be watched routinely, with defined follow up if the results are out of normal range.

As Dr. Cressey emphasized, fraud can be committed by the most ordinary of people: everyone is capable of being a fraudster under the right conditions. That’s what makes the opportunity leg of the Fraud Triangle so important. A good fraud risk prevention plan that controls opportunities for fraud works just when you need it.