People & Process – The Long Tail of the Fraud Triangle

Disclaimer: Portions of this conversation have been edited for length and clarity, and certain locations and details have been modified for privacy reasons.

In business, the concept of the Long Tail implies that an organization can find significant financial benefit selling small volumes of hard-to-find items to many niche customers. What began with statistical models in the 1950’s was popularized for a modern audience in a 2004 Wired Magazine article that highlighted the advantages of a digital economy where scale was just a matter of server space. Early adopters of a Long Tail business strategy included Netflix, Apple and Amazon.

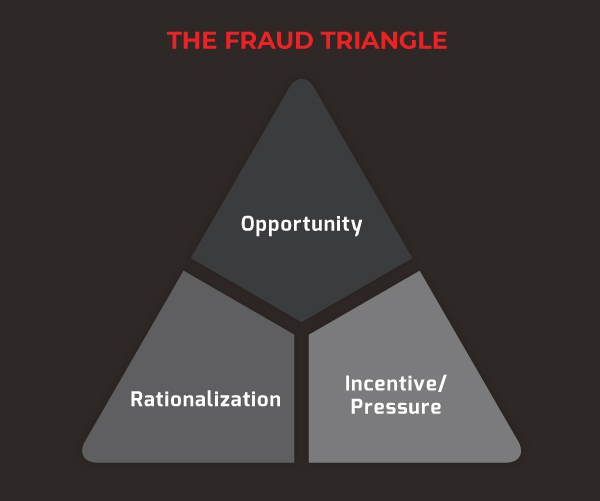

The Fraud Triangle brings together Pressure, Opportunity and Rationalization to explain WHY fraud happens; on the surface, it does not share overt similarities with the traditional definition of a long tail. However, in #OurStory this week, Keith Gray blends insights from an epic eight-figure fraud with a few lesser examples to highlight how both people and process actually ALLOW fraud to happen within what could arguably be described as the Long Tail of the Fraud Triangle. If we replace “small volumes of hard-to-find items to many niche customers” from the Long Tail definition with “fraudulent micro-actions within SOP gaps against specific financial entities,” we begin to see fraud’s own little economy where all the money is made.

Generally speaking, the primary frustration for organizations threatened by fraud is understanding which side of the triangle poses the most risk to their human capital. We know that strong cultures of workplace compliance resistant to fraud are not born overnight, and in 2020, nor are they forged in iron. The modern workplace (similar to the modern digital economy referenced in the Wired article) is no longer driven by a one-size-fits-all mentality (or “Top 10 mega hits,” as the head of the Long Tail is viewed). Updated social norms, evolving demographics and highly personal subjects like equity, justice, ownership and other influencing factors have actively changed our places of business. To create a compliance driven culture in today’s environment (COVID included) where security protocols become second nature may require organizations to do some deep thinking about how to apply these less “tangible” (but no less human) concepts to avoid the Long Tail of the Fraud Triangle – whatever that happens to look like for your organization.

For more tips, stories and insights about workplace security, you can visit our blog, check out our Resources page, follow Lowers & Associates on LinkedIn or contacts us.

In our work, we’re often called in to evaluate and investigate the aftermath of fraud. Is there anything that surprises you when reviewing these fraud cases?

Keith Gray: I wouldn’t say it’s surprising, but I think it’s always very interesting the lengths that people will go to in order to commit or sustain a fraud, complex or not. The Association of Certified Fraud Examiners has heavily researched the impact fraud has on the world economy, and it’s not insignificant. And unfortunately, what we see a lot, is that trust can lead to a lot of fraud. It’s unfortunate to present it that way, but a lack of controls and just the trust that people have with their employees often leads to opportunity to commit these frauds. Especially any time there are hard economic conditions, natural disasters, or pandemics like we’re dealing with now, that’s when it’s worst. It’s twofold, though: tough times provide an opportunity to commit fraud, but they’ve also actually helped us uncover fraud.

Case in point, around the time of the Great Recession, the owner of a large privately held company had been orchestrating a large, ongoing fraud. When the economy was booming, this person was able to move funds around, misappropriating entrusted funds for personal gain through real estate, financial investments, vehicles, various things. When the economy was doing well, this person could always cash out to make things right, it was always in their back pocket. What allowed this to happen was that this person was also able to manipulate the vaults and move money around, essentially playing a shell game with the vaults contents to pull the wool over the bank’s eyes or anyone that came in to audit the vault. There wasn’t a good, coordinated effort to come in and do full vault counts or things like that.

It’s also hard to imagine the recession being particularly helpful to any of this person’s investments, so why would doing a full vault count be important?

Keith Gray: As an independent auditor, we can go in and do a full vault count to get the whole picture. It’s exactly the type of thing we push for. An individual bank can go in, but they are only going to see their funds, allowing the opportunity for the fraudster to play a shell game. In this case, the economic downturn aided in the discovery of the fraud. When the country sank into a recession, much of the value in those investments disappeared, so this individual could not make up what was taken.

During this timeframe, one of the bank customers did get a little uneasy, alerting the authorities, and bringing the situation to light. The next thing you know, $90 million dollars is deemed to be missing. I spent about a year working that on behalf of a couple of clients, just trying to recreate it from the claim side.

That’s an eye-popping number. Is that what sticks with you most about this fraud?

Keith Gray: Well, our Director of Global Operations, Neil Watson, alluded to it in a previous blog but, as we do our work, every team member is informed by our experiences. As we go along, we continue to gain knowledge and it helps us evolve, sharpens our skills. For me, this case reinforces that going in, you can’t assume anything, you can’t believe anything until it’s confirmed or you’ve seen it with your own eyes. It reminds me to essentially be a sponge, to constantly be absorbing information as I go.

A lot of the time, you can find out there’s issues just by listening; people will give themselves away! For example, companies will ask us to come in on the back-end vault side, there may not be an absolute fraud, though a lot of times it is, but there’s clear process and control failures. On inspection, they might present something that shows they’re in balance at an individual branch location, but once you really dig in, it’s clear the data is being presented in an inconsistent way, perhaps leaving out some pieces.

For example, we have cases where our team will go in and count a million dollars, and they will then show us documentation to support that they’re holding a million dollars for 10 entities. On the surface it appears that they have physical control of the full value for which they have been entrusted; however, you then ask about the other two banks that aren’t being disclosed – which might be another half a million – so really, they’re short half a million dollars. But the way they present the information to corporate or ownership or management, they’ve been able to conceal that.

So, you just have to be independent, objective, not take anything for granted, listen and then start asking those questions to see if the whole picture makes sense. That’s big for us and our team’s approach.

What is the mentality of the people that commit these frauds? Do you find that the people have anything in common that drives their desire to perpetuate fraud?

Keith Gray: The Fraud Triangle is the why, but the how is the breakdown in controls or the misplaced trust. The commonality in that the thief or fraudster is given the opportunity. Greed is a real thing, and once they realize there’s an opportunity and they can get away with something a few times, I’ve seen a lot of frauds that have lasted 4 – 5 plus years without being discovered.

It usually starts when someone’s in a pinch, and the mindset is usually ‘I can make this right, I just need to pay a bill’ or something like that, and they plan to put it back with, say, a tax return. If that works out, maybe they don’t do it again, but in most cases, they do it again, and it’s still easy, and it evolves over years if left unchecked, from thousands of dollars to multimillion-dollar losses. It’s amazing how long and how much some fraudsters can get away with when there is zero independent oversight or SOPs.

What can you do in those situations? It seems like you really need to know who your employees are.

Keith Gray: Exactly. You have to make sure you know the person who has the keys to the castle – facility keys, alarm codes, vault combinations, CCTV access. A dedicated bad actor can manipulate anything, and once the SOP breakdowns start, greed takes over and they’ll go to any lengths at that point to conceal what they’ve done to their own company, peers and even clients.

One thing to look for is false reports to their customers. An individual might manipulate his or her employees, maybe take away responsibility saying, ‘Hey, I’ll take care of that’ or ‘It’s too confusing and hard to explain, so don’t worry about it.’ They’ll mess with people’s minds. To get around this, one of my first questions is always, ‘Can I see the HR records, the leave records, to see if they do take days off?’ And these people will go five years and never take a day off because they have to cover up their scheme. If they are in an accident and hospitalized or something, then it will come to light what they’re up to.

Whether it’s a long or short-term fraud, would you categorize these folks as “broken” people? Do they live in a different reality? Or is it as simple as, opportunity is as opportunity does?

Keith Gray: I wouldn’t necessarily say they were broken from the start. Frank Abagnale Jr., who spoke at our SCTA conference a few years ago, is a perfect example. What we see with him is that his mindset is educated and evolving. And most of these criminals have a similar mindset of gaining education as they go on and as they see how it works. And they get better and better at getting what they want.

So, whether they’re broken, they happen into it or they just got desperate, the why definitely evolves; some of these fraudsters like Frank are highly successful at being able to perpetrate schemes and have a genuine ability to hide or make the fraud look legitimate. It’s not what we’d see from organized crime, but rather just an average person looking for an opportunity.

If a local community non-profit needs a Treasurer, for example, and that role doesn’t pay anything, they might volunteer someone because s/he is a CPA who should be able to handle it. Well, yeah. It’ll get handled right out the door. It always shocks people how often that happens, but it happens because people want to like and trust other people. Regardless of that goal, if there’s not oversight or there’s not a real relationship with the person in that position or strong culture of compliance in place, that’s where organizations really run into trouble. It’s unfortunate we have to think that way, but it’s reality.